Decline & Revival After Independence

Tensions in the Church

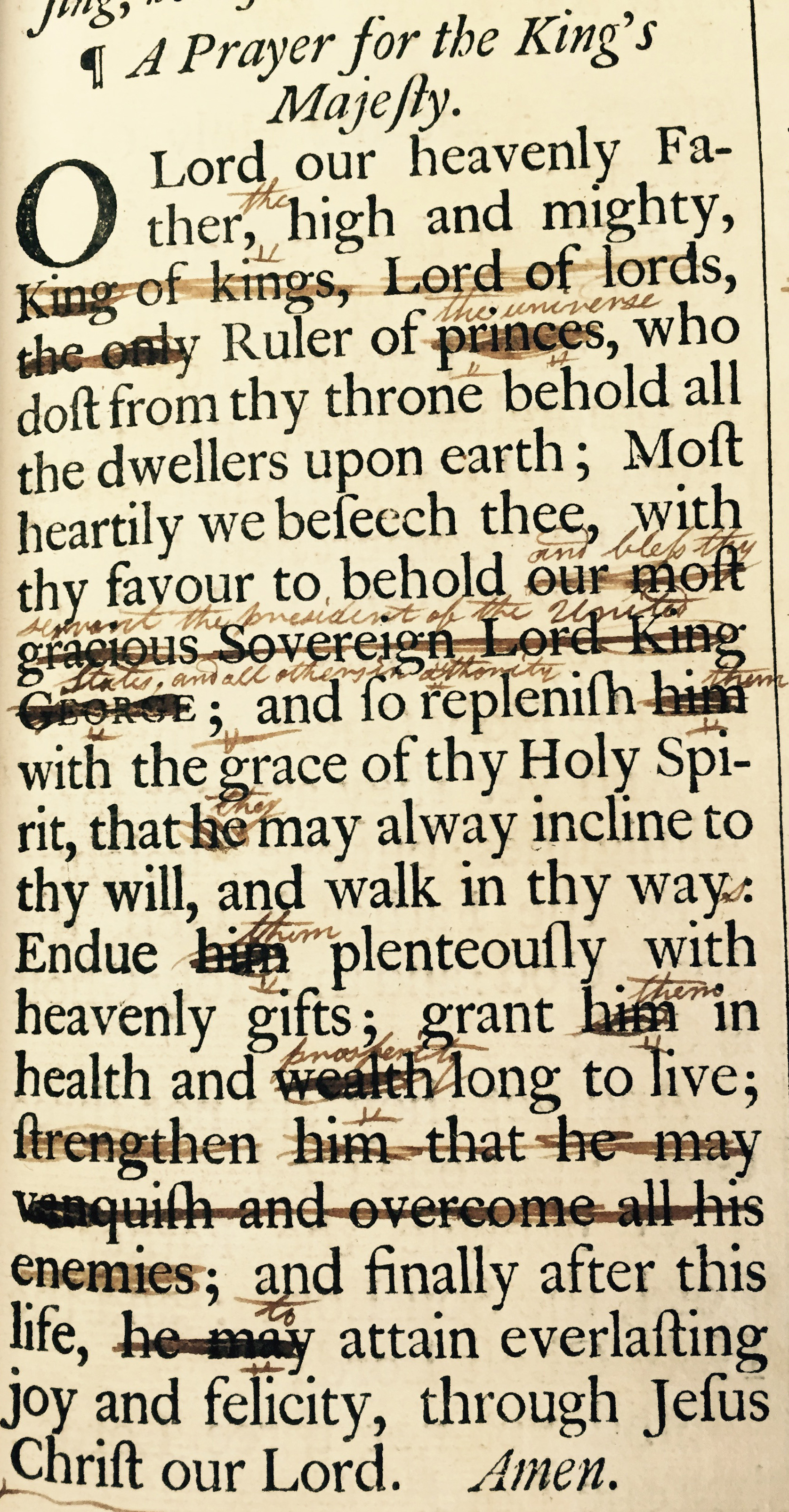

A copy of Aquia Church's 1662 Book of Common Prayer. After the Revolutionary War, one of the church's rectors crossed out parts of this prayer to reflect the new sovereignty of the United States. One change includes crossing out "our most gracious Sovereign Lord King George" to "and help thy servant the President of the United States, and all others in authority."

Although George Mason conveyed his wish that Rev. James Scott succeed Moncure as rector of Overwharton, it seems Rev. Scott stays in Prince William and the Rev. Clement Brooke from Maryland becomes the new rector. First signs of trouble occurred on November 22, 1766, when a group of dissenters signed a covenant establishing the Chopawamsic Baptist Church.[1] As the Church and the State were of one entity, the growing tensions between the colonies and Great Britain created exacerbated tensions between parishioners of the church. In July of 1775, the Governor of Virginia left the colony and "the members of the Assembly met as a Provincial Convention to raise and embody an armed force to defend the Province. The flight of the Governor left the Colony without an executive head and the Convention therefore appointed, on the sixteenth of August, a Committee of Safety."[2] Rev. Clement Brooke was chosen as one of two rectors to represent Stafford County on the Committee of Safety.[3] He did not last long, for dissent had broken out again among the parishioners of Overwharton Parish. On June 3, 1775, The House of Burgesses recorded yet another petition from the "sundry Inhabitants" of Overwharton, this time complaining that the "election of Vestrymen of the said Parish by Virtue of a late Act of the General Assembly, was made in an unfair and illegal manner" it was then ordered "for dissolving the Vestry of the Parish of Overwharton."[4] Brooke could not survive such a blow and left soon after to accept a position in Montgomery County.[5]

The Disestablishment of the Church of Virginia

By 1777, the colonies had declared their independence from Great Britain causing the need for states to form new bodies of government and assess their laws. A committee in Virginia was formed to help revise state laws which consisted of churchmen: George Mason, vestrymen of Truro Parish of Fairfax County, Thomas Jefferson, vestryman of St. Anne's parish of Albemarle County, Thomas Ludwell Lee, member of Overwharton Parish of Stafford County, George Wythe, Bruton Parish of Williamsburg, and Edmund Penleton, vestryman of Drysdale Parish of Caroline County. Together they edited Jefferson's Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom in Fredericksburg, VA based on Mason's earlier Bill of Rights, in which all Virginians had a "natural right" to freedom of religion.[6]

Jefferson's statute wouldn't become state law until 1786, by then, Virginians were interested in separating the church from the state flooding the Assembly with petitions from 1788 to 1799, "attacking the right of the Episcopal Church to hold title to her property" or glebe.[7] On January 22, 1799, the Assembly "repealed every law which in any way favored the Protestant Episcopal Church in Virginia, totally disestablishing it" and in December 1801, the Assembly enacted a law empowering the Overseers of the Poor to "seize glebes and endowment funds of land purchased by the Episcopal Church prior to January 1, 1777" where no rector was active.[8] This meant that glebes, which were at the time, the main source of income for rectors, would be seized once a rector of the parish died or left and churches could be seized if a "parish proved unable to maintain regular services in them."[9]

This proved to be the downfall for many colonial churches in Virginia. In the will of Rev. Robert Buchan, Overwharton's rector after Brooke, he anticipates these changes when he dies in 1803. He orders that his slaves be granted their freedom once the crop is finished and glebe sold. He does provide for them specifying that "they should be dismissed well clothed; and that each of them shall be furnished with an axe and a hoe, at the expense of the estate."[10] Overwharton's glebe, which had been willed to the church by Dr. Edward Maddox in 1694, was indeed taken from the church after Rev. Buchan's death when "Doctor Maddox’s descendants instigated suit claiming it was no longer being used as stipulated in his last will and Testament and recovered it."[11]

Rev. Buchan did not hold much hope for the future of an Episcopal Overwharton parish bequeathing "to my successor in the parish of Overwharton, if a minister of the Protestant Episcopal Church, my surplice; but if the parish should not obtain one of that persuasion, my executors may dispose of it as they think proper."[12] He had reason for pessimism, Aquia Church would not have rector for thirteen years and Potomac Church was abandoned after Rev. Buchan's death and burned by the British during the War of 1812.[13]

The Slow Revival

When the Right Rev. William Meade, the future Bishop of the Diocese of Virginia, was first ordained a deacon in 1811 at Bruton Parish in Williamsburg, he described the church as a "gloomy, comfortless aspect" in "wretched condition" with broken windows and the service itself was "cold and comfortless" with no sermon and only eighteen people gathered.[14] The state of the church is Virginia was so hopeless, when the Episcopal Church met in New Haven, CT that year, no one from the Virginia Diocese attended and the delegates officially expressed that "the church in Virginia is, from various causes, so depressed, that there is danger of her total ruin, unless great exertions, favored by the blessing of Providence, are employed to raise her."[15]

The first indications of a desire to revive Aquia Church is in 1817, when some local families begin to clean the church.[16] In 1819 Aquia receives a new rector, Rev. Thomas Allen who was also the rector of Dettingen Parish in Dumfries and shared his duties between the two churches. What followed was a long line of part-time rectors who worked to try to revive the congregation, fighting against steep odds of a declining population in Stafford County and the rise of the Methodist Church during the Second Great Awakening. Moncure Daniel Conway recalls how these national trends affected Overwharton parish:

"At the time of my parent's marriage, May 28, 1829, the Episcopal Church was nearly defunct in our Overwharton parish. Of its three churches, - Potomac, Aquia, and Cedar church in Falmouth, - the former had fallen into ruin, Aquia was without regular services, and Cedar church turned into a grain storehouse (ultimately swept away by a freshet). The Methodists occupied the county and preachers were sent by the Baltimore Conference. At the camp-meetings eloquent preachers from the cities assisted, and under one of these orators my father was "converted." His father was so chocked that a son should be carried away by what he regarded as vulgar fanaticism that a stormy scene ensued, and my father, who had barely reached his majority, left the paternal home. Grandfather speedily repented of his anger, but this touch of martyrdom brought to my father's side three of his sisters and two of his brothers. Thus it was that our family be Methodist."[17]

The Right Rev. Meade gives a detailed description of Aquia Church during his visits to the church in 1837 and 1838:

"In the year 1838, I visited Old Aquia Church as Assistant-Bishop. It stands upon a high eminence, not very far from the main road from Alexandria to Fredericksburg. It was a melancholy sight to behold the vacant space around the house, which in other days had been filled with horses and carriages and footmen, now overgrown with trees and bushes, the limbs of the green cedars not only casting their shadows but resting their arms on the dingy walls and thrusting them through the broken windows, thus giving an air of pensiveness and gloom to the whole scene. The very pathway up the commanding eminence on which it stood was filled with young trees, while the arms of the older ones so embraced each other it that it was difficult to ascend. The church had a noble exterior, being a high two-story house, of the figure of the cross. On its top was an observatory, which you reached by a flight of stairs leading from the gallery, and from which the Potomac and Rappahannock Rivers, which are not far distant from each other, and much of the surrounding country, might be seen. Not a great way off, on another eminence, there might be seen the high, tottering walls of the Old Potomac Church, one of the largest in Virginia, and long before this time a deserted one. The soldiers during the last war with England, when English vessels were in the Potomac, had quartered in it; and it was said to have been sometimes used as a nursery for caterpillars, a manufactory of silk having been set up almost at its doors. The worshipers in it had disappeared from the country long before it ceased to be a fit place for prayer. But there is hope even now for the once desolated region about which we have been speaking. At my visit to Old Aquia Church in the year 1837, to which I allude, I baptized five of the children of the present Judge Moncure, in the venerable old building in which his first ancestor had preached and so many of his other relatives had worshiped. He had been saving them for that house and that day."[18]

Through the hard work of Meade and other reformers of the Episcopal Church in Virginia, the church slowly began to gain membership. By the 1850s, the Episcopal Church had congregation sizes in the hundreds in larger cities, including Christ Church in Alexandria, St. James and St. Paul's in Richmond, and St. George's in Fredericksburg. Smaller churches began to feel the benefits of the growth of the church and during the 1854 Convention, J. C. Moncure, the church warden of Aquia Church, reported to diocese the grand restoration efforts:

"Since our last report to the Convention of 1853, Aquia church, in this parish, which was then reported as undergoing repairs, has been thoroughly repaired, at the expense of between $1500 and $2000, and is now on of the largest, handsomest and most commodious churches in the Diocese. This church, which was originally erected in 1751, is now the on Episcopal church in this county. For twenty years or more, it has been unoccupied; within the last five or six years, however, owing to the increase in the number of Episcopal families, by removals into this parish, the want of a place of worship agreeable to their preferences naturally suggested itself, ans the venerable old church was selected as the suitable point, both on account of position and the scared reminisces by which it was surrounded. We immediately went to work, and soon succeeded in raising the necessary amount, and completed the repairs during the last summer, in a neat and comfortable manner. We manifest the interest which we feel, when we report to the Convention, that we have, at quite a burthensome expense, provided a place of worship, and we are further willing and prepared to make provision for the adequate maintenance of a minister of the Word and Sacraments, if one suitable can be procured."[19]

This renewal of Aquia, and the growing prosperity of city churches, is exemplified in the gift of a large lectionary to Aquia Church from their neighboring church, St. George's in Fredericksburg. The inscription inside of the book reads, "Presented by the Rector and Vestry of St. George's Church, Fredericksburg, Va In token of Christian Fellowship - To Aquia Church, Overwharton Parish Stafford County Virginia January 1st 1854." The lectionary can be seen today, as it resides on the lower level of the pulpit. The Right Rev. Meade also celebrated the revival of the church, visiting in 1855, remarked, "had I been suddenly dropped down upon it, I should not have recognized the place or the building. The trees and brushwood and rubbish had been cleared away. The light of heaven had been let in upon the once gloomy sanctuary. The dingy walls were painted white and looked new and fresh, and to me it appeared one of the best and most imposing temples in our land."[20] The Rev. Henry Wall, the new rector of Aquia Church, St. James and Lamb's Creek Church in King George, reported to the Convention in 1856 that at the "fine old colonial church...the prospects are, in every way, encouraging."[21].